My Grandma Dorothy was a storytelling grandma. She moved to Santa Barbara when I was four or five, and babysat us many Friday evenings. I still remember lying in the dark on my bunk bed, Grandma on the twin bed with Kristi, and her voice as she told stories about growing up on the farm in Kalispell. The barn dances, the cold winters, summers on Lake Blaine, caring for the animals, the time the pigs were intoxicated by the rotten apples that she and her siblings threw into the pen.

Those stories would be enough, but they are not all that I have.

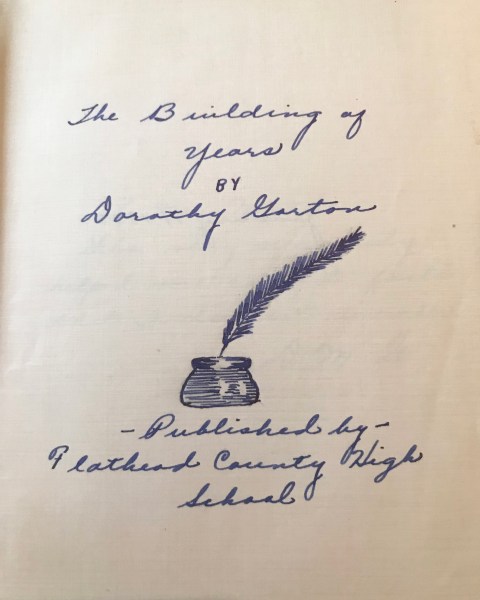

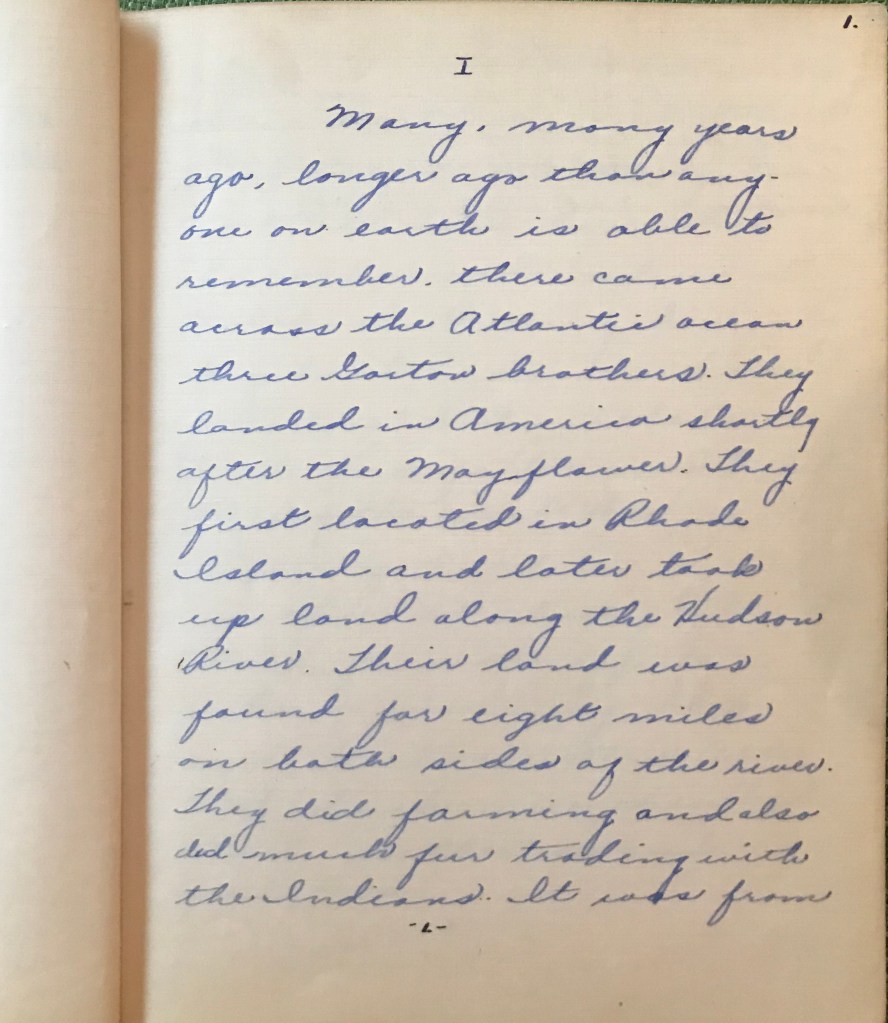

When she was a senior in high school, Dorothy wrote an autobiography for a school project. She entitled it The Building of Years, and in it she chronicled the family history she knew, as well as details from her childhood. It is a priceless treasure.

The book is charming, with its black binding and page after page of her neat script in blue pen. She added a few illustrations in ink, as well as several photos. There are occasional additions on the facing pages as she corrected information or added details later in her life.

She dedicated the book to her mother, who “very sincerely helped me collect facts that I do not remember.” So, I have my great grandmother, Thelma Gorton, to thank as well. She also writes, “In this book I have preserved facts of my former ancestry and also many little incidents of my life this far.”

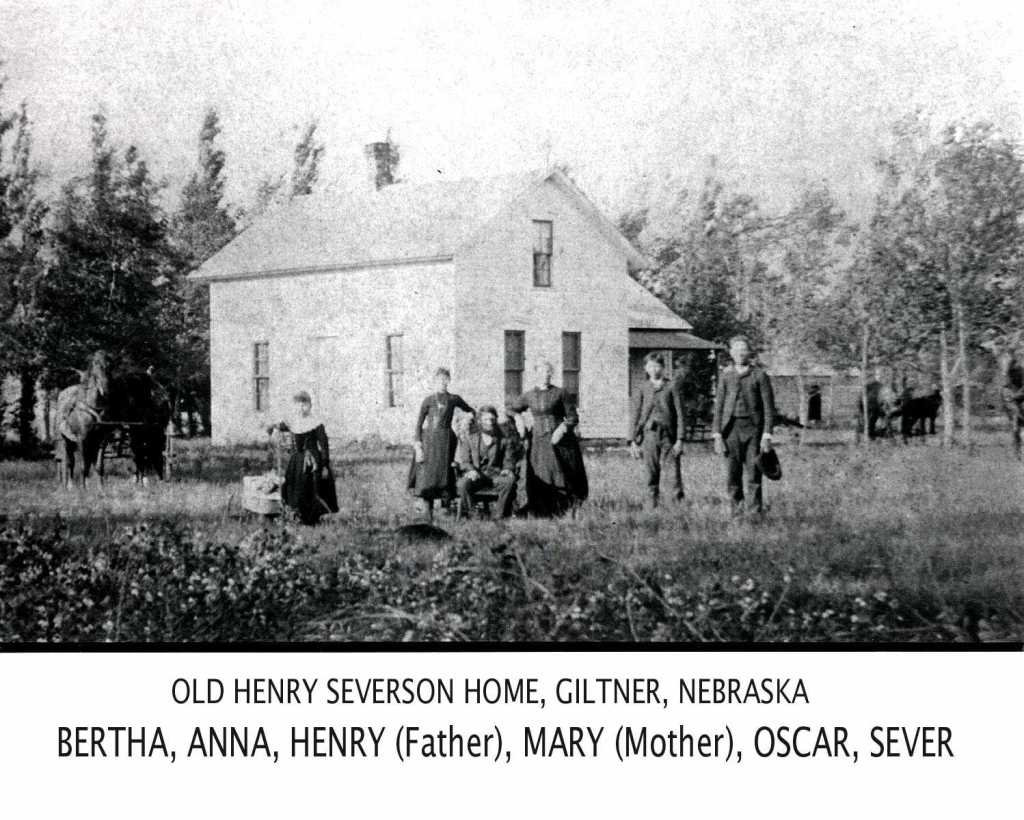

Dorothy begins her book, “Many, many years ago, longer ago than any one on earth is able to remember, there came across the Atlantic ocean three Gorton brothers. They landed in America shortly after the Mayflower. They first located in Rhode Island and later took up land along the Hudson River. Their land was found for eight miles on both sides of the river. They did farming and also did much fur trading with the Indians.” And indeed, this is true. Samuel Gorton arrived in 1636 in New England, with his wife Mary and their three children. His story is well-documented, and has many twists and turns I will describe in another post. I love that my grandmother was aware of this hundreds-year-old history, and celebrated it in her own account.

It is this rootedness in story that characterizes most of my memories of my grandmother. I have another of her journals that chronicles the next chapters of her life, and it is another of my greatest treasures. I spent many months transcribing it, grateful that I learned at an early age to read her scrawling cursive.

Grandma Dorothy’s life on the farm in the twenties and thirties seemed as removed from my own as the Little House books, but she always made the stories live. I am aware, as I read her account of her early life, that my own seems sometimes too current to be interesting–and yet, in fifty or eighty years, it will seem old-fashioned. I am becoming aware of the value of recording a few details of my own life and experiences, hoping that a future granddaughter will find a connection in trips to the beach, watching scurrying crabs and hermit crabs, or in time spent curled in a chair snuggled next to my giant St. Bernard.

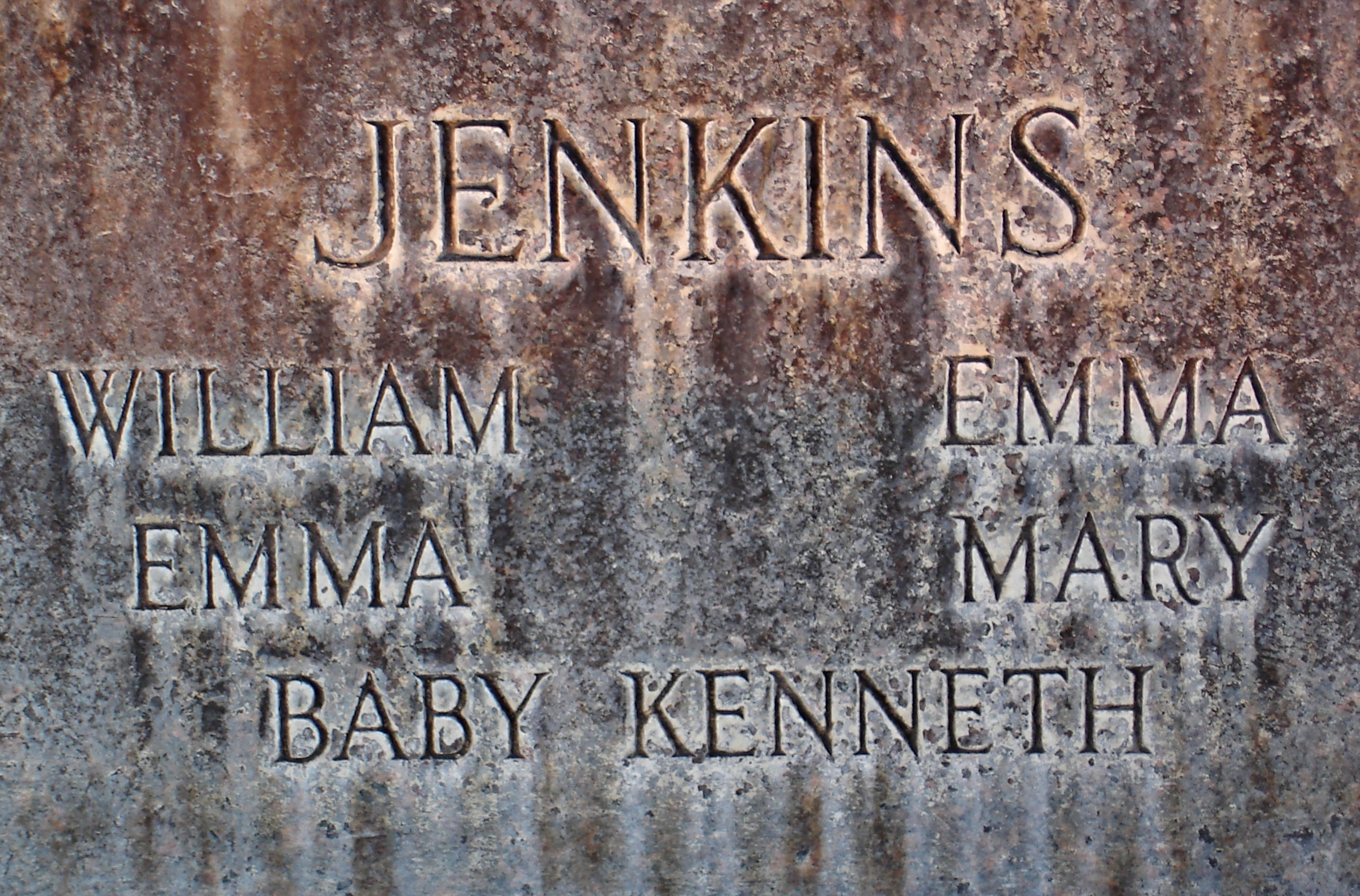

I am also aware of the great family legacy present in story. Not all of the stories are easy or good. Parents and children who died too young, ravaged by disease and war; tales of financial loss at the hands of swindlers or in the wake of failed crops; pain caused by favoritism or misunderstanding. But these experiences and the stories that followed have shaped generations of family, and play their significant role in making me who I am.

The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when William was eighteen years old. A week and a half later, on April 27, 1861, William enlisted, serving a three-month term with Co. G, 15th Regiment. He then mustered in again as a private in October of 1861 with the Pennsylvania 7th Cavalry, with which he served for the rest of the war. His service record was as follows: Mustered in as private, October 22nd, 1861. Re-enlisted as a veteran, November 1863. Promoted to Corporal, to Second Lieutenant. December 1st, 1864. Mustered in December 18th, 1864, to Captain, July 24th, 1865. Mustered August 10th, 1865. Mustered out with company. Macon, Ga., August 23rd, 1865.

The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when William was eighteen years old. A week and a half later, on April 27, 1861, William enlisted, serving a three-month term with Co. G, 15th Regiment. He then mustered in again as a private in October of 1861 with the Pennsylvania 7th Cavalry, with which he served for the rest of the war. His service record was as follows: Mustered in as private, October 22nd, 1861. Re-enlisted as a veteran, November 1863. Promoted to Corporal, to Second Lieutenant. December 1st, 1864. Mustered in December 18th, 1864, to Captain, July 24th, 1865. Mustered August 10th, 1865. Mustered out with company. Macon, Ga., August 23rd, 1865.