I was watching a show on Netflix the other day–Ghost Town Gold, in which two guys visit the kinds of ghost towns my family poked around in on vacations. But instead of looking for cool rocks like we did, they go into old barns and buildings and come out with fabulous historical artifacts. In this particular episode (Season 1, Episode 1, around the 30 minute mark), the two hosts explored the town of Austin, Nevada.

Austin rang a bell. Was that where my 3x- Great Grandfather had mined silver? I pulled up the family tree.

But first, a little back story.

On April 12, 1852, nine-year-old William Jenkins arrived in the harbor of New York City on the ship Pathfinder. His family, including his parents William and Elizabeth, brother John (age 14), and sister Anna (age 3), had moved from Wales to seek new opportunities. In her family history, my grandmother recorded: “They settled in St. Clair, Pennsylvania, where his parents lived for the rest of their lives. His father, William Jenkins, St., died soon after they settled in Pennsylvania, but his mother lived until after she was ninety years old. She lived in a little white house by herself and always kept a white pig. She was a very clean old lady and always gave the pig a scrubbing every Saturday.” This last detail is all the more significant when you realize that St. Clair was a coal mining town, and that spotless old lady was a coal miner’s wife.

The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when William was eighteen years old. A week and a half later, on April 27, 1861, William enlisted, serving a three-month term with Co. G, 15th Regiment. He then mustered in again as a private in October of 1861 with the Pennsylvania 7th Cavalry, with which he served for the rest of the war. His service record was as follows: Mustered in as private, October 22nd, 1861. Re-enlisted as a veteran, November 1863. Promoted to Corporal, to Second Lieutenant. December 1st, 1864. Mustered in December 18th, 1864, to Captain, July 24th, 1865. Mustered August 10th, 1865. Mustered out with company. Macon, Ga., August 23rd, 1865.

The Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when William was eighteen years old. A week and a half later, on April 27, 1861, William enlisted, serving a three-month term with Co. G, 15th Regiment. He then mustered in again as a private in October of 1861 with the Pennsylvania 7th Cavalry, with which he served for the rest of the war. His service record was as follows: Mustered in as private, October 22nd, 1861. Re-enlisted as a veteran, November 1863. Promoted to Corporal, to Second Lieutenant. December 1st, 1864. Mustered in December 18th, 1864, to Captain, July 24th, 1865. Mustered August 10th, 1865. Mustered out with company. Macon, Ga., August 23rd, 1865.

William Jenkins was eighteen when he began his military career, and twenty-two when the war ended. At some point during or after the war, William married Emma Lewis, whose family had immigrated from England and also moved to St. Clair. Emma’s father was a coal miner, too, and she was listed in the 1860 census as being a seamstress at the age of 16.

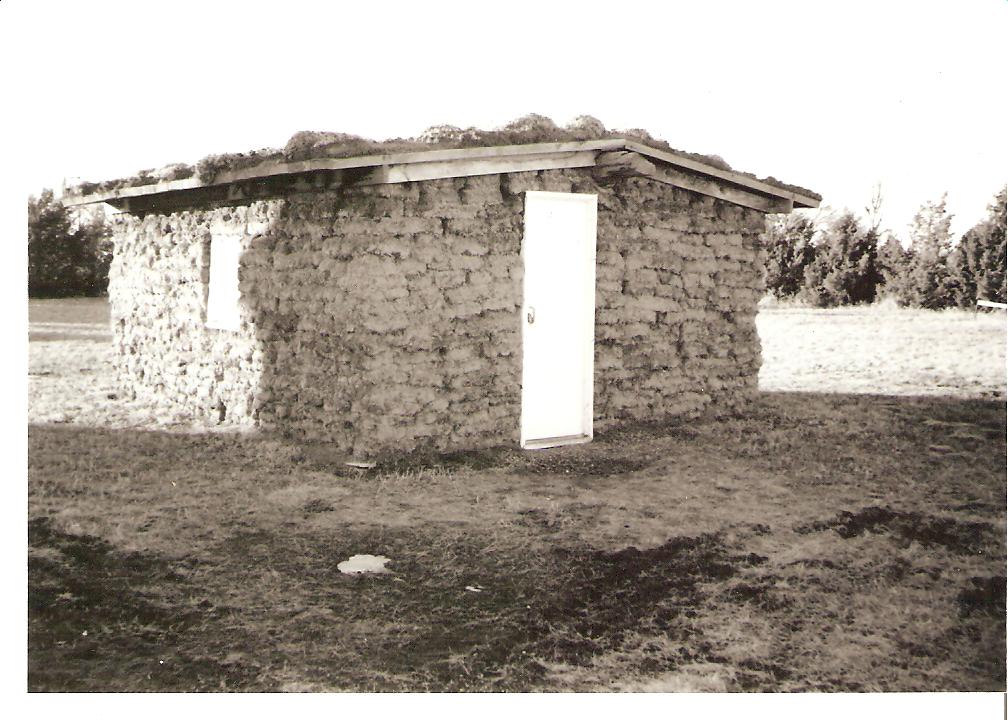

While there is little external data for the period immediately following the Civil War for this family, my grandmother’s journal fills the gap. She reports, “They made their home in St. Clair and to them were born three children. It was at this time that the West was being opened and the newspapers were headed with “New Gold Mines in the West,” and “Get Rich Quick in the West.” As William Jenkins was interested in mining and also to get rich quick, he went to the Tonapah mines in Nevada. The mines looked very successful to him so he sent for his wife and children to come to Nevada to make their home. Their journey was made by railroads as far as there were railroads, and the rest of the way by stagecoach. Mrs. Jenkins had heard of the wild West robbers and Indians. She had a number of gold certificates to bring along and was afraid that she would be robbed of them. After much thinking she sewed them into her baby’s clothes.”

It seems to me that William settled back in St. Clair after the War and they had three children. It is possible that they had been married on one of his furloughs from service. In any case, according to this family history, William and Emma had at least a couple of children before they headed west. The story of Emma sewing the gold bonds into her baby’s clothes suggests that there was at least one child born to them by this point; I wonder if there might have been just one baby who rode the stagecoach with her, or whether she had one or two toddlers in tow as well.

When the family was recorded in the 1870 census, they had settled in Austin, Nevada. (My grandmother’s account above refers to the Tonapah mines, but those were not named and active until about thirty years later.) The census records three family members: William, Emma, and four-month-old Sara Ann, who had been born there in Austin.

What had happened to the other children?

“The town was progressing peacefully until an epidemic of Scarlet Fever swept the country. There were few doctors and they were many miles from the town. Many people lost their lives and among them were the three children of Mr. and Mrs. Jenkins. This was a very tragic experience to them and took all of the happiness out of their life for a long time.” My grandmother goes on to suggest that the reason the family moved to Butte, Montana, was to escape the sadness of the loss of their children.

That may be. I tried for years to get more information on these children–their names, or even simply when they lived. Sometimes I wondered–was this story conflated with that of other pioneer family members?

The 1900 census didn’t shed any additional light. That census was the first which asked women how many children they had borne, and how many of those children were living. The record stated that she had three children, and all were living. This would be Sara (1870), Emma (1874) and Harold (1886).

Then I found the entry for Emma Jenkins in the 1910 census. Her husband had died five years before, and she was living with her son Harold, his wife and young child, and her widowed daughter Sara. Emma’s answer gave me, for the first time, the evidence I was looking for. Number of children: seven. Number living: three.

There they were. No names, no dates, but historical evidence that they had lived and were remembered.

Then I took a closer look at her headstone.

Places for William and Emma.

And then three children: Emma, Mary, and Baby Kenneth.

These are not her grown children. This must be a memorial to the children who were lost: Emma, Mary, and Baby Kenneth.

Somehow, I feel closer to my great, great, great grandmother, knowing that after her husband died, she entered the memory of these little ones into the census record and preserved their names on her tombstone.

I told them about Lake Blaine and the big family picnics when we got together with my aunts and uncles and cousins and how some of my girl friends and I went camping there. That was where we all learned to swim and where I had my first boat ride. I told them about the depression.

I told them about Lake Blaine and the big family picnics when we got together with my aunts and uncles and cousins and how some of my girl friends and I went camping there. That was where we all learned to swim and where I had my first boat ride. I told them about the depression. commercial flying license or 200 hours of flying time. That was what gave us our start and led us out of Montana and eventually to the San Francisco Bay Area where he became an airline pilot and helped to start an airline.

commercial flying license or 200 hours of flying time. That was what gave us our start and led us out of Montana and eventually to the San Francisco Bay Area where he became an airline pilot and helped to start an airline.