My dad, James W. Brown, has been writing some wonderful stories, prompted by a brilliant gift from my sister Kristi. I asked if we could include his stories here, to keep everything in one place, and he readily agreed. So, I would like to introduce this guest post by one of my favorite storytellers of all time.

After my father’s training in Minneapolis to learn how to run the operational side of an airline, our family was again reunited in the San Fernando Valley as the world emerged from WWII. I didn’t see much of my father since he was heavily involved in starting a new airline and a new type of airline from scratch.

The Valley was still largely rural at that time and housing was very scarce. We were crammed into a house with at least one or two other families. I don’t remember much from that time but I do remember that one of our housemates woke up the whole house from time to time with a blood-curdling scream! He had been a fighter pilot whose plane was shot down over the Pacific and in the long, descent into the ocean the cockpit was filled with fire. He managed to parachute before the flaming fighter hit the sea but relived the terror in nightmares from which he awoke sweating and screaming.

Next, I remember living in a motel near Palo Alto separated from the two or four lanes of Highway 101 by only a gravel parking lot.

Finally, we moved into an old farmhouse out on the mudflats of East Palo Alto. Our nearest neighbor was an old gentleman who lived on his chicken ranch down the road, Mr. Pearson. Mr. Pearson had lots of cats and kittens on his ranch to keep the rats and other pests under control; too many cats. From time to time he would gather up a batch of kittens, put them in a gunny sack, and drown them in a rain barrel. I saved more than one of these cute little creatures by running home and begging my mother to let me have him for a pet. “Please, Mom—Mr. Pearson’s going to drown him!”

I remember helping my Mom do the laundry in a washing machine that had a “wringer” attached. The wringer was a pair of crank operated rollers what would squeeze the water out of the clothes as you took them out of the washer and ran them “through the wringer” before hanging them on the clothesline to dry. Mom warned me not to get my fingers near the wringer, lest they be caught and crushed!

On Saturdays the few kids from the neighborhood would sometimes gather on the bunk bed in my room to listen on the radio to “The Lone Ranger”, “Sky King”, “The Green Hornet” and such fare.

We were one of the first families to have a television set and I remember sitting in front of the set watching the “KPIX” test patten on the black and white screen waiting for “It’s Howdy Doody Time” to come on the air.

Transportation was hard to come by, too. I believe that we had the usual Chevy convertible, but my Dad also acquired an old Model A Ford to commute to San Francisco Airport, where he now was headquartered. I don’t know if the Model A had a starter motor, but I do know that it had a hand crank up front and that starting it was almost as tricky as starting an airplane: you had to “advance the spark” and maybe even fiddle with the hand throttle while someone out front hand-cranked the engine to get it going.

Meanwhile, a relatively small group of very creative Southwest Airlines employees worked day and night to set up the navigational systems required by a scheduled airline. A genius radio man, Ed Rein, and his crew established a network of navigational aids on the West Coast from Oregon to L.A. The system relied heavily on an instrument in the airplane called an automatic direction finder (ADF). An ADF is like a compass dial in that it is a round instrument containing a needle like the hand of a compass which points at the location of a radio station. If the station is straight ahead, the needle points to “0°” and if the station is off the right wingtip the needle points to “90°”. If you keep the needle pointing at “0°” you will fly directly over the radio station. If you tune the ADF to a second radio station it will tell you the direction to that station. The point where the lines from the 2 radio stations intersect is your position. The ADF could point at a commercial radio station like KGO-AM (“810 on your dial”) in San Francisco or a special navigational radio station. As Southwest Airlines’ chief pilot my Dad flew these routes in Southwest DC-3 aircraft to evaluate and test the systems before they were submitted for certification and put into service. These wonky electrical engineers were not beyond an occasional practical joke themselves. My Dad was well known for his ability to “grease” a DC-3 onto the runway with such finesse that you couldn’t tell you had landed. The jokesters thought that it would be great fun to all gather in the front of the DC-3 passenger cabin and then, just as the airplane flared for a perfect 3-point landing (the DC-3 was a “tail-dragger”) they would all run to the back of the cabin to shift the weight so drastically that it would spoil the landing. But they never succeeded—at least as I recall the story told to me by Mr. Rein.

As the chief pilot, it was my Dad’s responsibility to give a “6-month check ride” to each of the airline’s captains to be sure that they maintained sharp flying skills. He would, occasionally, allow me to go along on a check ride as the sole passenger in the DC-3’a cabin. The check-ride would put the captain (and the airplane) through its paces and push both to the limit to be sure the captain could handle any emergency, or “unusual attitude” encountered. The captain would don a “hood” which prevented seeing outside the cockpit so that maneuvers must be performed solely by looking at the instrument panel. He was required to perform semi-aerobatic maneuvers such as steep turns with the wingtip pointing straight at the ground and “power-on” stalls where the airplane is put into such a steep climb that it feels like it is pointing almost straight up. Eventually, the airplane slows down so much that the wing can no longer generate enough lift to support flight. That’s called a “stall”. At that point the nose of the airplane drops precipitously and the airplane dives until it regains enough speed to fly again. To the airplane’s occupants, it feels like going over the top of a roller coaster. It is a pretty violent maneuver even when the airplane’s propellers are throttled back to an idle. With “power-on” it is an awesome maneuver. In a twin-engine commercial airliner it is beyond awesome. I loved it.

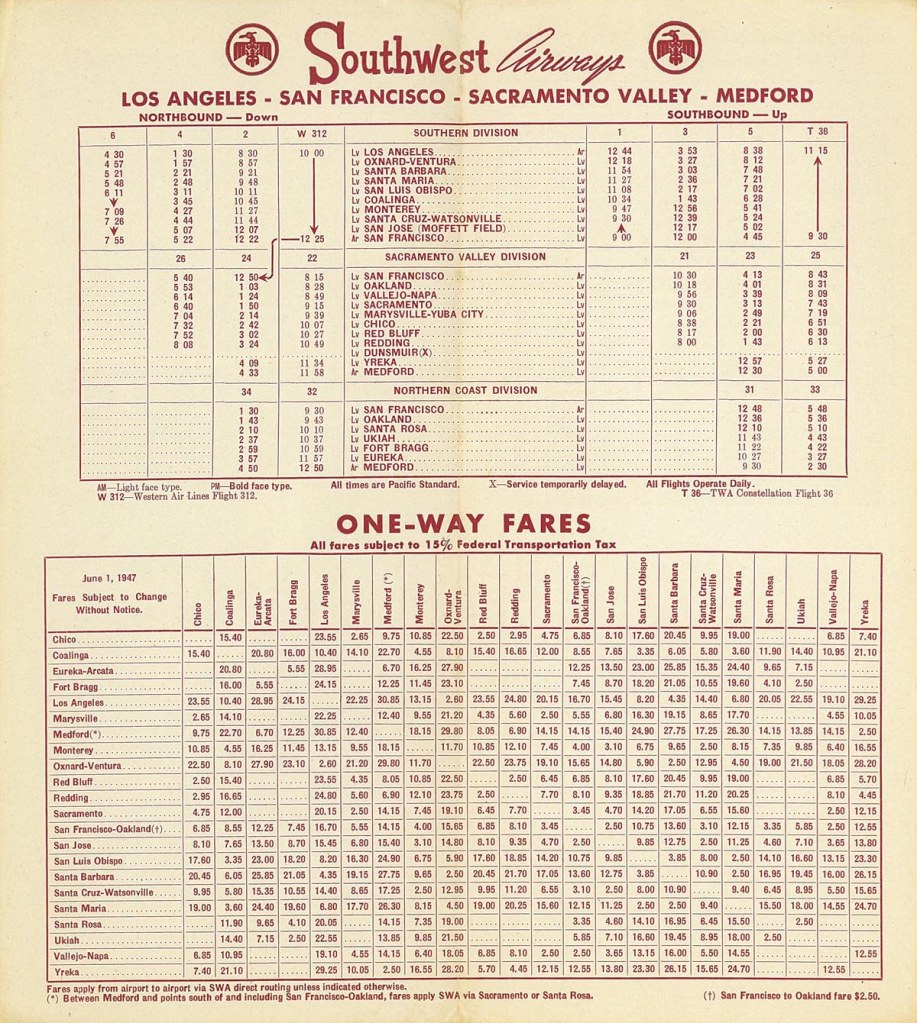

Southwest Airlines was one of the first and most successful of the “feeder airlines” as they were called. They served small cities from where they carried passengers to larger airports from which the transcontinental (“trunk”) airlines like United, American, and TWA carried them on longer routes. Virtually all of the feeder airlines flew fleets of DC-3s, the ubiquitous workhorse called the C-47 by the military, produced by the thousands for WWII transport and paratroop service and plentiful after the war as “war surplus” for civilian use.

Southwest was highly creative in its use of the DC-3. They perfected the “stair door” that opened from the top so that it formed a stairway for passengers to enter the airplane. Because the DC-3 was a “taildragger” the rear portion of the fuselage was low to the ground and the “stair door” was a quick and easy entrance to the passenger cabin.

In some ways, Southwest was like the early railroad trains that crossed the American plains in the 19th century making “whistle stops” along the route just long enough for a few passengers to jump on board. Southwest could slip the DC-3 into the airstrip of a small town and be back in the air in 5 minutes. How they did it was ingenious. As the captain taxied up to the little passenger terminal building, he would shut down the left engine so the propwash wouldn’t blow the boarding passengers away, but leave the right engine running so that he didn’t need an external electrical source to start the engines. As the plane rolled to a stop, the purser would open the stair door so passengers could deplane or board. Then the station agent would march the passengers out to the plane with military precision, help them board and handle the luggage through the baggage door at the rear of the plane. When the passengers were belted in, as the stair door was closed, the captain would fire up the left engine, taxi away, push the throttles wide open as he rolled onto the runway and be back in the air seconds later. There weren’t likely any other airplanes around the lonely airstrip, so they were always “number one for departure.”

Business was good, and Southwest wanted to start replacing the venerable DC-3s with more modern airplanes, like the Martin 404 with its tricycle landing gear which was rapidly replacing the older taildraggers. Japan Airlines had a used Martin 404 for sale. The only problem was that it was in Japan. No problem, for the little “can-do” airline. They dispatched my Dad to Japan to pick up and ferry the airplane to San Francisco for refitting into the pride of their fleet! Ferrying a two-engine airplane across the North Pacific is not for the faint-hearted. They stripped all the seats and partitions out of the fuselage and filled it with extra fuel tanks for the long flight far beyond the 404’s normal range. Undaunted by the challenge, my Dad and his co-pilot took off from Japan. My Dad had even purchased gifts in Japan for the family: a complete set of Noritake china for my Mom and the fanciest, heaviest Japanese bicycle you have ever seen for me. Once in the air, the 404 proved to be a well-used airplane indeed, with a worrisome miss in the left engine that kept the sole occupants, the two pilots, on the edge of their seats as they nursed the rough running airplane to the mainland.

I remember that starting a radial piston engine from a cold start, as they did when starting a flight from a major terminal like San Francisco, was quite a ballet. The captain started the right engine first. A ground crew member stood near the engine with a portable fire extinguisher. An auxiliary gas powered electrical power generator was plugged into the engine. The captain adjusted the throttle and fuel mixture controls and engaged the starter motor to prime the engine as the copilot counted the number of propeller blades rotating past his window. When the copilot had called out the number of blades needed to prime the engine the captain would call out “contact” and flip on the ignition switch and play the throttle and mixture controls until the big radial, belching copious clouds of smoke, would sputter, then roar to life. Then they would repeat the ballet until all engines were running. An engine didn’t always start on the first try! Starting all four engines on one of the big airlines’ transcontinental flights was quite a show.

When it was placed in service, my Dad, as the No. 1 seniority pilot, generally flew a Martin 404 schedule. The family home then was in Santa Clara, not too far from the San Jose municipal airport. I would sometimes ride my bicycle to the airport to see my Dad as his flight landed and departed. On rare occasions, he would signal the ground crew to escort me to the airplane and I would enter the cockpit through the forward door in front of the cabin. A temporary seat (occasionally installed for a check pilot to observe and evaluate the pilots) could be installed just behind the pilot and co-pilot. I vividly remember one flight in particular. At that time United Airlines was competing with the “feeder” airlines on some of United’s shorter routes with the Convair 440 aircraft. The Convair 440 was a twin-engined propeller driven plane with two big radial engines, just like the Martin 404. In fact, the planes looked so much alike that the inexperienced observer could confuse the two. On one competing route, United flew the Convair to San Francisco with a stop in Monterey. Southwest flew the Martin 404 on the same route, but with an additional stop in San Jose. United scheduled its flight to depart Monterey and come through the Saratoga gap in the Coast Range at the same time that Southwest was climbing out of San Jose so that their flight paths converged at the south end of San Francisco Bay. On this particular flight I was sitting on the jump seat where I could see out the cockpit windows. Sure enough, off to the left I could see the United Convair coming through the gap and starting its descent for SFO. The Martin 404, under full takeoff power, was climbing to cruise altitude for the short flight. Dead ahead was the southern tip of San Francisco Bay with the Dumbarton Bridge stretching across the bay a few miles ahead like a great finish line. The significance of the Dumbarton Bridge was that it was where airliners were allowed to contact the San Francisco air traffic control tower to request clearance to land and ask for the inside of the two parallel runways, shortening the taxiing distance and arriving at the gate first. With two captains urging maximum performance out of a combined four big radial piston engines, it was an exhilarating experience. I can’t honestly say that I remember who was first to call the tower for clearance, but I know that “Red Hot Henry Brown” didn’t like to come in second.

I remember one other time when I was sitting on the jump seat. It was on a stormy night flying into Los Angeles International Airport. Today’s airplanes—even single engine private planes—have beautiful, big visual displays that make instrument landings pretty simple. It wasn’t so easy 70 years ago. Flying in cloud I couldn’t see anything but the misty red reflection of the flashing wingtip navigational lights. I had on a headset from which I heard the steady tone of a radio signal. What seemed to be a steady tone, really wasn’t. It was a combination of 2 tones being sent in a narrow, directional beam by 2 radio transmitters at the end of the runway. One transmitter was transmitting in the letter “A” in Morse Code (dot-dash). The other transmitter was transmitting the letter “N” (dash-dot). In the narrow directional beam where the two letters overlapped, the “A” and “N´ combined to produce neither—only a steady tone. That’s what I was hearing because we were “on the beam”. If the aircraft drifted a little to the right or left of the beam, you would begin to hear a faint “A” or “N” letting you know that you were drifting off course. That’s how you stayed on course. Another equally quaint system let you know if your approach was on the proper “glide path” to arrive at the end of the runway and not too short or too long. A radar beam was directed down the glide path that gave the altitude of the target. An air traffic controller on the ground communicated this vital information to the pilot with a continuous message, “On glide path”…”10 feet below glide path” and so forth and the pilot would slightly adjust the throttles to stay on the glide path. Finally, we broke out below the low clouds and could see the bright runway lights straight ahead and on a perfect glide path. It sounds simple enough but on a dark and bumpy night with so many “souls on board” behind you, you know that you’ve put in a good day’s work when the wheels kiss the tarmac, and you taxi safely to the gate.

The era of the “feeder” airlines has closed replaced by the corporate subsidiaries of the few remaining major airlines flying fast little regional jets that, with the least experienced, lowest seniority pilots, do the most “real flying” left in the commercial aviation industry.